- News

- UBC School of Music’s Eshantha Peiris on Diego El Cigala

UBC School of Music’s Eshantha Peiris on Diego El Cigala

The Chan Centre partners with the UBC School of Music’s Department of Ethnomusicology to engage students in writing short pieces connecting our presentations to pertinent ideas and concepts in ethnomusicology. Below, graduate student Eshantha Peiris writes about the importance of Diego El Cigala’s music in a cultural and political context.

As well as studying ethnomusicology, Eshantha Peiris performs with Sri Lanka-based bands Thriloka and Baliphonics. He recently released an album of solo piano music, entitled Global Rhythms Reimagined.

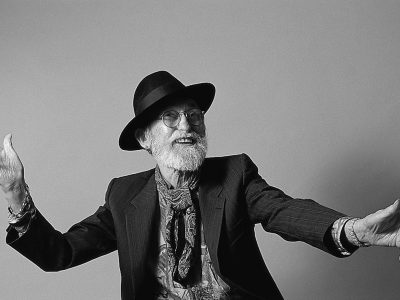

Hailing from a Gitano (Spanish Romani) family of flamenco musicians from Madrid, Spain, Diego El Cigala’s rise to international stardom has coincided with the increased visibility of the Latin GRAMMY Awards in recent times. El Cigala had already earned respect as a legitimate flamenco cantaor early in his career (first by singing behind well-known flamenco dancers, and later as a solo singer); however it was his collaboration in 2003 with Cuban pianist Bebo Valdes that brought him international recognition and his first Latin GRAMMY win (for ‘Best Traditional Tropical Album’). His Latin-jazz-influenced nuevo flamenco album ‘Picasso En Mis Ojos’ won him a Latin GRAMMY in 2006 for ‘Best Flamenco Album’, and his exploration of Argentinian song in ‘Cigala & Tango’ was declared ‘Best Tango Album’ in 2011. A second award in the ‘Tango’ category was a result of the album ‘Romance de la Luna Tucumana’, El Cigala’s most recent musical venture, which fuses Argentinian song with Cuban rhythms, and is the focus of his current concert tour.

From the view of an ethnomusicologist, performances by musicians such as El Cigala present an opportunity to examine the various layers of cultural meaning brought into focus by multicultural creativity. Musical hybrids resulting from recent waves of global migration, as well as the legacy of the 1970s’ self-aware jazz fusions, have ensured that ethnomusicologists can no longer afford to make broad generalizations about isolated musical cultures. Instead, fusion music can provide a good backdrop for discussing the nuanced issues of musical genre, race, capitalism, and their inherent power relationships.

“From the view of an ethnomusicologist, performances by musicians such as El Cigala present an opportunity to examine the various layers of cultural meaning brought into focus by multicultural creativity.”

Thinking about genre from a music-theory point of view could lead to an analysis of the various musical elements of a song, and looking at where these elements may have come from. Examining the past may reveal a long history of foreign influences on flamenco music [i][ii] (and vice versa [iii]), in a way defending El Cigala’s innovations from the inevitable protests of flamenco purists [iv]. El Cigala’s current fame as a vocalist could also be seen as reflecting flamenco’s history as a genre that was defined by singing (in contrast with the present-day spotlight on flamenco dancing) [v].

When considering issues of race, it might be observed how members of the (historically oppressed) Roma minority play a disproportionally prominent role as professional musicians in Spain [vi], and how their flamenco music has moved from the fringes of society to become a national symbol of their country. Questions can be asked about historical identity and cultural heritage, and about the expectations that global audiences may have when performers are marketed in different ways. (El Cigala himself has suggested that suffering – along with being a gitano – is the defining characteristic of singing flamenco [vii].)

While the modern global capitalist music industry has given musicians and audiences a chance to imagine alternative identities for themselves [viii] (as evident in El Cigala’s recent launch of his own record label, and migration to the Dominican Republic), it can also be seen by some as a standardizing machine which requires pandering to popular tastes. And while noting that El Cigala’s informed choices regarding genre mixing and collaborative artists have gained him new audiences in the Americas (arguably the same audience base catered to by the Latin GRAMMY awards), an ethnomusicologist will usually be most interested in accounting for the changing social conditions which allow for these artistic decisions to be made in the first place.

[i] “Flamenco”. Accessed October 9, 2014. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Flamenco

[ii] Tony Bryant. “Styles influenced by Flamenco”. Andalucia.com. Accessed October 9, 2014. http://www.andalucia.com/flamenco/styles-influenced.htm

[iii] Ed Morales. The Latin beat: the rhythms and roots of Latin music from Bossa Nova to Salsa and beyond. Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2003.

[iv] “Diego El Cigala”. Andalucia.com. Accessed October 9, 2014. http://www.andalucia.com/flamenco/musicians/el-cigala.htm

[v] see [i]

[vi] Peter Manuel. “Flamenco in Focus – An analysis of a performance of Soleares”, In Analytical studies in world music, ed. Michael Tenzer. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. 2006.

[vii] Josh Kun. “Defending the Ancient Heartbeat of Flamenco”. The New York Times, September 7, 2004. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/07/arts/music/07bebo.html

[viii] Ingrid Monson. “Riffs, Repetition and Theories of Globalization” Ethnomusicology 43 (1) p. 31-65. 1999.